By BUKAR Mohammed

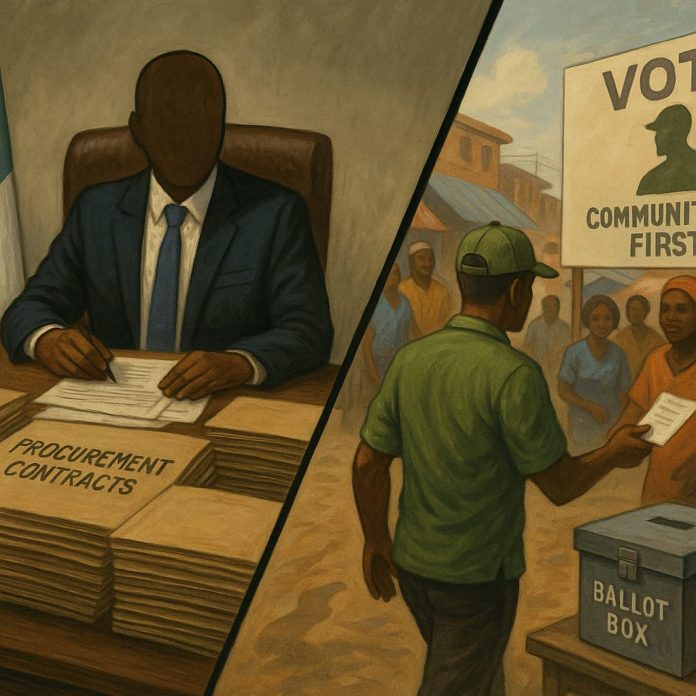

In Nigeria’s evolving political landscape, federal appointments have increasingly shifted from being platforms for national service to springboards for personal political advancement. A growing number of federal appointees now leverage their positions not only to shape public policy but to build campaign structures, secure funding pipelines, and consolidate regional influence ahead of electoral contests.

A critical avenue through which this is done is public procurement—long recognized as a high-risk zone for corruption and elite capture. In recent assessments, it is estimated that Nigeria loses approximately $18 billion annually to corruption and financial crimes related to procurement, representing about 3.8% of the country’s GDP. With public procurement accounting for an estimated 10–25% of GDP, the potential for diversion of resources is immense.

Empirical studies confirm that agencies led by political appointees often suffer performance drops, increased opacity, and reduced oversight—particularly when those appointees have known political ambitions. These figures are not just statistical abstractions—they point to a deeper structural problem. Control of procurement channels, especially in revenue-generating sectors like transport, infrastructure, and natural resources, offers appointees the tools to quietly build war chests while operating under the guise of service.

Although Nigeria has made strides in procurement transparency through e-Government Procurement (e-GP) and open contracting data portals, gaps in enforcement, behavioral accountability, and systemic opacity continue to provide cover for abuse. While digital reforms reduce some manual interference, they have not sufficiently disrupted entrenched networks of influence or the politicized awarding of contracts.

Governance experts describe this scenario as state capture—a condition in which public institutions are manipulated by political elites to serve narrow, self-serving goals rather than the collective public interest. The consequence is clear: weakened institutions, hollow service delivery, and widespread disillusionment with government.

To mitigate this, Nigeria must move beyond reform on paper and implement targeted oversight in practice.

Anti-graft agencies must begin proactive scrutiny of federal officials—especially those with visible political aspirations—who oversee procurement-intensive agencies. Red flags such as inflated contracts, unexplained spikes in procurement activity, or a concentration of awards to opaque vendors in pre-election cycles should trigger forensic audits and public disclosure.

This recommendation is not about stifling ambition. It is about safeguarding national institutions from being converted into personal campaign machinery. Without clear accountability mechanisms, federal offices risk becoming silent enablers of political fundraising—undermining their credibility and weakening trust in public service.

To restore that trust, Nigeria must draw a clear line between governance and political maneuvering. Public procurement must remain a tool for delivering value to citizens—not a hidden currency for electoral advantage.

BUKAR Mohammed is a Policy Analyst from Kano

Share your story or advertise with us: Whatsapp: +2347068606071 Email: info@newspotng.com