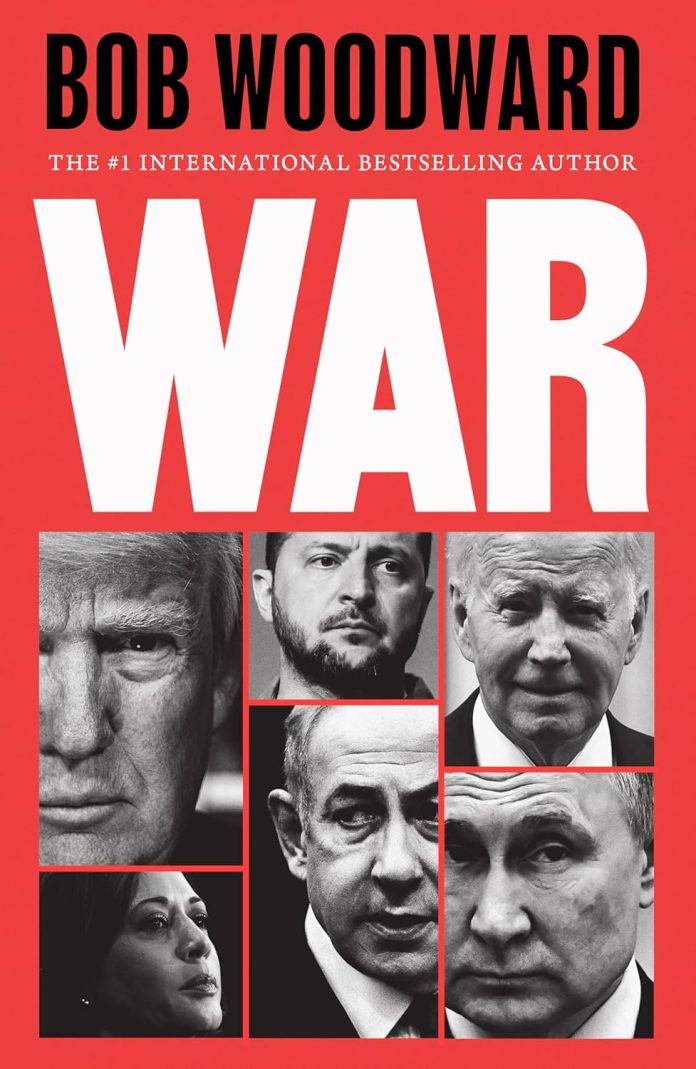

Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Bob Woodward in his latest book WAR, tells the revelatory, behind-the-scenes story of three wars—Ukraine, the Middle East and the struggle for the American presidency. In this chapter, Woodward paints a picture of Russian president Vladimir Putin as a wanna-be Messiah who used the period of COVID to research and get the inspiration to battle Ukraine and bring it back into the Soviet Union. I enjoyed reading this book by a famous journalist who has authored twenty-two bestselling books. Excerpt:

****

A month after the Geneva summit, Putin placed another gun on the table.

In a starkly personal and bellicose 5,000-word diatribe published on July 12, 2021, Putin argued Ukraine had never existed as an independent country.

National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan read the President’s manifesto as a declaration of the inner Putin, who he was and what he wanted to do.

“Russians and Ukrainians are one people—a single whole,” Putin began. “Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians are all descendants of Ancient Rus, which was the largest state in Europe.” And since the 9th century, he continued, Kyiv was considered “the mother of all Russian cities.”

“The formation of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state,” Putin said, “is comparable in its consequences to the use of weapons of mass destruction against us.”

His tone self-righteous and academic, Putin erased the existence of Ukraine as a separate country, a people with their own history, beliefs, culture and language.

“Therefore, modern Ukraine is entirely the product of the Soviet era. We know and remember well that it was shaped—for a significant part—on the lands of historical Russia,” Putin said. “Russia was robbed.”

When Sullivan read through Putin’s manifesto his first thought was “Covid.”

U.S. intelligence reporting showed that during the pandemic, Putin had been changed by intense and prolonged isolation. He had surrounded himself with a small coterie of trusted people of similar nationalistic views who became a feedback loop. Those who wanted to see him in person had to quarantine for weeks. He was physically and metaphorically separated from Russian society for nearly three years.

One of the central figures in Putin’s inner circle was Yury Kovalchuk, a Russian billionaire reputed to be Putin’s personal banker. He had known Putin since the 1990s and appeared to share the messianic worldview that Putin espoused in his manifesto.

Another Putin confidant was Father Tikhon, an Orthodox priest with a similarly imperialistic view of Russia. Then there were the Rotenberg billionaire brothers—Arkady Rotenberg and Boris Rotenberg, who owned the largest construction company for gas pipelines in Russia.

Other people learned Irish step dancing in quarantine, Jake Sullivan joked, but Putin went deep into Russian history.

Sullivan had heard that during a phone call between Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Putin said you wouldn’t believe the stuff that I’ve been finding in the Russian archives.

It was clear to Merkel that Putin had spent a lot of his time in isolation just digging around in the archives, taking things out, studying ancient maps.

Taking Ukraine had become kind of a fever dream during his Covid isolation. But the fever didn’t pass. It didn’t break.

Sullivan and his deputy Jon Finer took the manifesto seriously, but it didn’t strike them as an alarm bell or a declaration of war. More than anything, they viewed it as typical Putin. The Russian leader was known for his long philosophical rants, historical fabrications, and absolute refusal to acknowledge Ukrainians independent existence. But still it was puzzling and unsettling for its intensity. A topic of curiosity and even disgust.

Sullivan had spend the last year reading up on Russian history and trying to understand Putin’s almost neurotic obsession with Ukraine. The formation of Russia, the deeply rooted grievances, the chip on Putin’s shoulder, the relationship with Europe, with NATO, the sense of needing central control, the Mongols taking Moscow in the mid-13th century, Putin’s desire to be a messiah in Russian history like Peter the Great, Catherine the Great. All of it.

After reading Putin’s manifesto, National Security Council Russia director Eric Green found it unusual for a sitting Russian president to go into such depth. Was Putin just trying to get something off his chest? Was this something he wanted to use as an exercise or a way of explaining Russia’s view of things? Or would Putin’s essay actually inform Russia’s actions?

“I think it speaks to Putin’s disillusionment with the Ukrainian government and his attempt to start to delegitimize it,” Green said. “Putin wants his prophecy about Ukraine being a failed state, he wants that to come true.”

“Ukraine used to possess great potential,” Putin said in his essay. “Step by step, Ukraine was dragged into a dangerous political game aimed at turning Ukraine into a barrier between Europe and Russia, a springboard against Russia.”

The biggest country in Europe, Ukraine was also an important buffer between Russia and Europe.

Putin called Ukraine’s leaders “neo-Nazis”—President Zelensky was Jewish—and leveled a long list of accusation against them and the West for pursuing an “anti-Russia project.”

“We will never allow our historical territories and people close to us living there to be used against Russia,” Putin warned. “And to those who will undertake such an attempt, I would like to say this way they will destroy their own country.”

For CIA director Bill Burns, who had served as ambassador to Moscow from 2005 to 2008, the manifesto was reminiscent of many of his conversations with Putin over the years. “There was nothing really new it,” Burns believed. Some of it is dressing up a conviction which is mostly at its core about power and what Russia believes it is entitled to do, he said. Then you dress it up with a lot of history—selectively.

Over in the Pentagon, Undersecretary for Defense Colin Kahl had read intelligence that Putin actually believe the things he had written—that Ukraine is not a real country and Ukrainians are all just Russians.

“Putin was not a fan of the Soviet Union,” Kahl said, “but he still saw the collapse of the Soviet Union as the biggest crime of the 20th century and believed that the Russians had been serially stabbed in the back since then.”

Kahl saw the essay as another showcase of Putin’s imperial ambition. “He dreams of reconstituting a Russian empire and there is no Russian empire that doesn’t include Ukraine,” he said.

“It’s always weird to read things like that as an American,” Kahl added, “because our history doesn’t go back very far. So the notion that countries would give a shit about what happened 9,000 years ago or whatever or, you know, 2,000 years ago or 1,000. Americans don’t think like that.”

Share your story or advertise with us: Whatsapp: +2347068606071 Email: info@newspotng.com