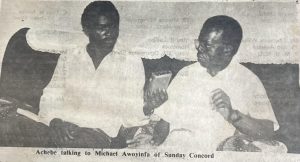

‘Things Fall Apart Nearly Stolen From Me’(By Mike Awoyinfa, first published in Sunday Concord Magazine of November 6, 1983)Chinua Achebe was lucky. Perhaps he wouldn’t have been the prominent novelist that he is today.

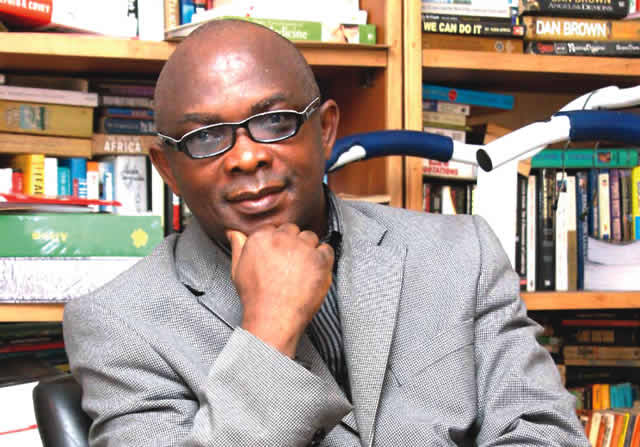

The manuscript of his first novel, the all-time classic Things Fall Apart got lost. It was nearly stolen from him! The budding novelist then in his twenties, had finished writing the manuscript which he wrote by hand, and he needed someone to type it out nicely “so that it would be attractive to a publisher,” Achebe told me. It was in the mid-fifties. At that time, it wasn’t easy in Nigeria to find a typist or a typing agency that could type a whole book. So young Chinua Achebe posted the manuscript to a typing agency in London. It was the only copy he had. The agency received the manuscript. They wrote asking for payment which Achebe did promptly. It was after then that things started falling apart between the typing agency in London and the obscure, aspiring novelist in Lagos where he worked as Talks Producer for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. He waited and waited for several months. He checked the post office every day in the hope that the script would arrive. But it never did. No longer at ease, the anxious and worried young man wrote several letters to the agency, enquiring about the manuscript, but they didn’t reply. Fortunately, Achebe knew someone in London at the BBC whom he had earlier shown the script. So he wrote to the person who then phoned the typing agency over the script. Not only that, an English lady in Lagos, Mrs. Angela Beaty, whom Achebe describes as a “tough and no-nonsense woman” was going to London on holidays. She took up the matter. In London, the typing agency people started framing excuses. “We sent it but the Customs returned it saying it wasn’t wrapped,” an official there told Mrs. Beaty. “So we wrapped it properly and sent it back. It is on the high seas.” “Can I see your dispatch book?” the tough Mrs. Beaty demanded. They couldn’t produce the dispatch book. Mrs. Beaty then threatened to make trouble with them if after the next few months Chinua Achebe did not receive the scripts. Something scandalous was brewing. It was no longer the case of an obscure writer in Africa whose manuscript could be stolen with impunity. Eventually, Achebe got his typed scripts and the manuscript after a few more months of perplexity. Recalling the episode, Achebe told me it would have been suicidal if the manuscript had been stolen. “I would have died,” he said dramatically. “Died? You mean you wouldn’t have been able to rewrite it?” I asked.“No. Not that particular book. I don’t think I would have died but I would have been terribly…I don’t know.”Chinua Achebe, 53 (in 1983), had matured from the twenty-eight-year-old novelist who brought honour to his country Nigeria by writing Things Fall Apart, regarded as “the first novel of unquestioned literary merit” to emerge from Anglophone West Africa. His hairstyle is still the same, but a substantial portion of it greying. His eyes popped from his gold-rimmed glasses perched on his nose as he spoke in a soft, husky voice that was barely audible at times. Things Fall Apart (1958) is a taut novel written simply, depicting the rise and fall, like a Greek tragedy of a self-made chieftain Okonkwo who finds it hard to accept the values of a new social order, a new dispensation brought by the English missionaries and colonial administrators into the land of the Igbos. He dies in the end by committing suicide rather than conforming to the new order. At the time that novel was published, it was greeted with rave reviews in literary circles all over the world. Critics claimed Chinua Achebe as Africa’s finest novelist. Wrote a critic, Bernth Lindfors: “No African novelist writing in English has yet surpassed Achebe’s achievement in Things Fall Apart, except Achebe himself.” Another critic, Arthur Ravenscroft, wrote: “For technical inventiveness both in language and novelistic technique, for profound insight into tragic human experience, for satirical sophistication, and for sustained creative energy, Achebe must still be regarded as the Anglophone African novelist of most considerable stature.” In less than a decade from 1958 to 1966, Achebe had turned out three more novels of merit, although some of them, in the view of critics, surpasses the height reached in Things Fall Apart. In 1960 came No Longer at Ease which reads like a postscript or a sequel to Things Fall Apart. In it, Achebe depicts Okonkwo’s grandson, Obi, educated in Europe, and living in the 1950s. He is caught in a similar conflict as he tries to reconcile the values of African tradition with European values. In the end, he falls tragically to the influence of corruption. Chinua Achebe in Arrow of God returns to the past, to the period of his people’s contact with the white man’s rule and he comes out with the evocation of traditional Igbo culture far richer than he does in Things Fall Apart. In his fourth and last novel so far, A Man of the People, published in 1966, Achebe ventures into satire. Using an anti-hero, Odili, using the first person narrative form, Achebe lampoons the political corruption and thuggery of Nigeria’s first republic. The book ends with a military coup which prophetically coincided with the first military coup in Nigeria, executed the same year that Achebe published his book, thereby opening up the suspicion that he had knowledge of the coup. He didn’t. After A Man of the People came the drought. Achebe didn’t write another novel. Rather, he concentrated on writing short stories, poems and essays—literary and politically. His political essay dealing with the political problems of Nigeria is titled Trouble with Nigeria.With his novels, Achebe has carved for himself the reputation of an artist who is careful, fastidious, simple yet elegant, and in full control of his language. As a pioneer, he has blazed a trail in the field of African literature. Achebe is not only a novelist treating readers with fascinating plots, he is a historian chronicling the story of his people undergoing conflicts of social change. Remarked one critic: “Achebe’s novels read like chapters in a biography of his people and his nation since the coming of the white man.” Not only is Achebe a historian, he sketches the traditional way of life of his people, during the olden days, far more vividly and far more comprehensively than any sociologist or anthropologist could have. For each novel, he carefully chooses the most suitable style. And he has the gift of a skilled ventriloquist in his ability to individualize his characters by differentiating their speech. For example, the way a village elder in Achebe’s novel speaks is not the same as a white colonial officer does. Achebe has devised the style of vernacular English which stimulates the idioms and expressions of the Igbo language in their originality. Notable also is the frequent use of proverbs and similes which helps to evoke the cultural milieu of his narratives. “Among the Igbos,” Achebe once said, “the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are spoken.” So many of Achebe’s similes and metaphors have become popular in modern usages. Examples: “like bushfire in the harmattan,” “like a bad cowry,” “like a lizard fallen from an Iroko tree.”In a way, Achebe, through his literary works, has contributed to the wave of nationalism that surged in West Africa throughout the fifties and sixties. Talking of nationalism, Chinua Achebe said he used to be called Albert, but he discarded the name out of nationalistic consciousness to adopt his Igbo name of Chinua, the short form of Chinualumogu. (To be continued).

The manuscript of his first novel, the all-time classic Things Fall Apart got lost. It was nearly stolen from him! The budding novelist then in his twenties, had finished writing the manuscript which he wrote by hand, and he needed someone to type it out nicely “so that it would be attractive to a publisher,” Achebe told me. It was in the mid-fifties. At that time, it wasn’t easy in Nigeria to find a typist or a typing agency that could type a whole book. So young Chinua Achebe posted the manuscript to a typing agency in London. It was the only copy he had. The agency received the manuscript. They wrote asking for payment which Achebe did promptly. It was after then that things started falling apart between the typing agency in London and the obscure, aspiring novelist in Lagos where he worked as Talks Producer for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. He waited and waited for several months. He checked the post office every day in the hope that the script would arrive. But it never did. No longer at ease, the anxious and worried young man wrote several letters to the agency, enquiring about the manuscript, but they didn’t reply. Fortunately, Achebe knew someone in London at the BBC whom he had earlier shown the script. So he wrote to the person who then phoned the typing agency over the script. Not only that, an English lady in Lagos, Mrs. Angela Beaty, whom Achebe describes as a “tough and no-nonsense woman” was going to London on holidays. She took up the matter. In London, the typing agency people started framing excuses. “We sent it but the Customs returned it saying it wasn’t wrapped,” an official there told Mrs. Beaty. “So we wrapped it properly and sent it back. It is on the high seas.” “Can I see your dispatch book?” the tough Mrs. Beaty demanded. They couldn’t produce the dispatch book. Mrs. Beaty then threatened to make trouble with them if after the next few months Chinua Achebe did not receive the scripts. Something scandalous was brewing. It was no longer the case of an obscure writer in Africa whose manuscript could be stolen with impunity. Eventually, Achebe got his typed scripts and the manuscript after a few more months of perplexity. Recalling the episode, Achebe told me it would have been suicidal if the manuscript had been stolen. “I would have died,” he said dramatically. “Died? You mean you wouldn’t have been able to rewrite it?” I asked.“No. Not that particular book. I don’t think I would have died but I would have been terribly…I don’t know.”Chinua Achebe, 53 (in 1983), had matured from the twenty-eight-year-old novelist who brought honour to his country Nigeria by writing Things Fall Apart, regarded as “the first novel of unquestioned literary merit” to emerge from Anglophone West Africa. His hairstyle is still the same, but a substantial portion of it greying. His eyes popped from his gold-rimmed glasses perched on his nose as he spoke in a soft, husky voice that was barely audible at times. Things Fall Apart (1958) is a taut novel written simply, depicting the rise and fall, like a Greek tragedy of a self-made chieftain Okonkwo who finds it hard to accept the values of a new social order, a new dispensation brought by the English missionaries and colonial administrators into the land of the Igbos. He dies in the end by committing suicide rather than conforming to the new order. At the time that novel was published, it was greeted with rave reviews in literary circles all over the world. Critics claimed Chinua Achebe as Africa’s finest novelist. Wrote a critic, Bernth Lindfors: “No African novelist writing in English has yet surpassed Achebe’s achievement in Things Fall Apart, except Achebe himself.” Another critic, Arthur Ravenscroft, wrote: “For technical inventiveness both in language and novelistic technique, for profound insight into tragic human experience, for satirical sophistication, and for sustained creative energy, Achebe must still be regarded as the Anglophone African novelist of most considerable stature.” In less than a decade from 1958 to 1966, Achebe had turned out three more novels of merit, although some of them, in the view of critics, surpasses the height reached in Things Fall Apart. In 1960 came No Longer at Ease which reads like a postscript or a sequel to Things Fall Apart. In it, Achebe depicts Okonkwo’s grandson, Obi, educated in Europe, and living in the 1950s. He is caught in a similar conflict as he tries to reconcile the values of African tradition with European values. In the end, he falls tragically to the influence of corruption. Chinua Achebe in Arrow of God returns to the past, to the period of his people’s contact with the white man’s rule and he comes out with the evocation of traditional Igbo culture far richer than he does in Things Fall Apart. In his fourth and last novel so far, A Man of the People, published in 1966, Achebe ventures into satire. Using an anti-hero, Odili, using the first person narrative form, Achebe lampoons the political corruption and thuggery of Nigeria’s first republic. The book ends with a military coup which prophetically coincided with the first military coup in Nigeria, executed the same year that Achebe published his book, thereby opening up the suspicion that he had knowledge of the coup. He didn’t. After A Man of the People came the drought. Achebe didn’t write another novel. Rather, he concentrated on writing short stories, poems and essays—literary and politically. His political essay dealing with the political problems of Nigeria is titled Trouble with Nigeria.With his novels, Achebe has carved for himself the reputation of an artist who is careful, fastidious, simple yet elegant, and in full control of his language. As a pioneer, he has blazed a trail in the field of African literature. Achebe is not only a novelist treating readers with fascinating plots, he is a historian chronicling the story of his people undergoing conflicts of social change. Remarked one critic: “Achebe’s novels read like chapters in a biography of his people and his nation since the coming of the white man.” Not only is Achebe a historian, he sketches the traditional way of life of his people, during the olden days, far more vividly and far more comprehensively than any sociologist or anthropologist could have. For each novel, he carefully chooses the most suitable style. And he has the gift of a skilled ventriloquist in his ability to individualize his characters by differentiating their speech. For example, the way a village elder in Achebe’s novel speaks is not the same as a white colonial officer does. Achebe has devised the style of vernacular English which stimulates the idioms and expressions of the Igbo language in their originality. Notable also is the frequent use of proverbs and similes which helps to evoke the cultural milieu of his narratives. “Among the Igbos,” Achebe once said, “the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are spoken.” So many of Achebe’s similes and metaphors have become popular in modern usages. Examples: “like bushfire in the harmattan,” “like a bad cowry,” “like a lizard fallen from an Iroko tree.”In a way, Achebe, through his literary works, has contributed to the wave of nationalism that surged in West Africa throughout the fifties and sixties. Talking of nationalism, Chinua Achebe said he used to be called Albert, but he discarded the name out of nationalistic consciousness to adopt his Igbo name of Chinua, the short form of Chinualumogu. (To be continued).

Share your story or advertise with us: Whatsapp: +2347068606071 Email: info@newspotng.com