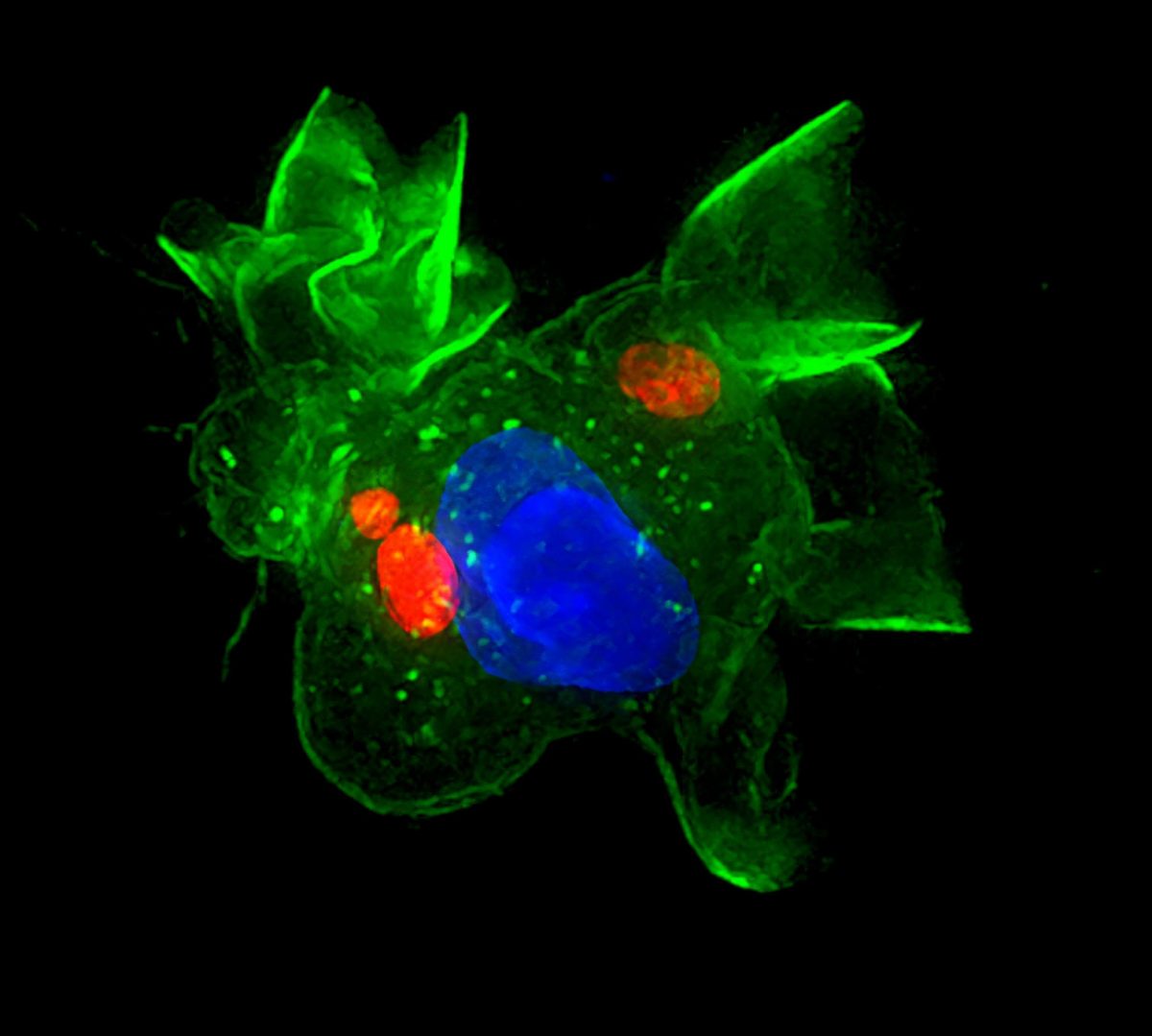

The image shows an immune cell that has been infected by Toxoplasma parasites (red). The surface of the cell is colored green and the nucleus of the cell is blue. Credit: Antonio Barragan

A large portion of people on the planet is infected with the parasite Toxoplasma. Now, a study headed by scientists at Stockholm University demonstrates how this tiny parasite spreads so successfully throughout the body, for example to the brain. The parasite infects immune cells and hijacks their identity. The research was recently published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

The various roles of immune cells in the body are very strictly regulated in order to combat infections. How Toxoplasma infects so many people and animal species and spreads so quickly has long been a mystery to scientists.

“We have now discovered a protein that the parasite uses to reprogram the immune system”, says Arne ten Hoeve, a researcher at the Department of Molecular Biosciences, Wenner-Gren Institute at Stockholm University.

According to the research, the parasite injects the protein into the immune cell’s nucleus, changing the cell’s identity. Immune cells are deceived by the parasite into believing they are a different kind of cell. This alters the immune cell’s gene expression and behavior. Toxoplasma causes infected cells that should not travel in the body to move quickly, allowing the parasite to spread to different organs.

Multiple immune cells that have been infected by Toxoplasma parasites (red). The surface of the cell is colored green and the nucleus of the cell is blue. Credit: Antonio Barragan

Toxoplasma has been described as converting immune cells into Trojan horses or wandering “zombies” that spread the parasite. The recently published research provides a molecular explanation for the phenomenon and demonstrates how the parasite is much more targeted in its spread than previously thought.

“It is astonishing that the parasite succeeds in hijacking the identity of the immune cells in such a clever way. We believe that the findings can explain why Toxoplasma spreads so efficiently in the body when it infects humans and animals,” says Professor Antonio Barragan, who led the study, which was carried out in collaboration with researchers from France and the USA.

Information regarding the parasite Toxoplasma and the disease toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is probably the most common parasitic infection in humans globally. Toxoplasma also infects many animal species (zoonosis), including our pets. The WHO has estimated that at least 30% of the world’s human population is a carrier of the parasite. Studies indicate that 15-20% of the Swedish population carry the parasite (the vast majority without knowing it). The incidence is higher in several other European countries.

Felines, not just domestic cats, have a special place in the life cycle of Toxoplasma: it is only in the cat’s intestine that sexual reproduction takes place. In other hosts, for example, humans, dogs, or birds, reproduction takes place by the parasite dividing.

Toxoplasma is spread through food and contact with cats. In nature, the parasite spreads preferentially from rodents to cats to rodents and so forth. The parasites are “sleeping” in the rodent’s brain and when the cat eats the mouse, they multiply in the cat’s intestine and come out via the feces. The parasite ends up in the vegetation and when the rodent eats the vegetation it becomes infected. Humans become infected through meat consumption or through contact with cats, specifically cat feces.

The parasite causes the disease toxoplasmosis. When a person is infected for the first time, mild flu-like symptoms occur that can resemble a cold or the flu. After the first infection phase, the parasite transitions to a “sleeping” stage in the brain and begins a chronic silent infection that can last for decades or for life. The chronic infection usually causes no symptoms in healthy individuals. Toxoplasma can, however, cause a life-threatening brain infection (encephalitis) in people with a weakened immune system (HIV, organ transplant recipients, after chemotherapy) and can be dangerous to the fetus during pregnancy. Eye infections can occur in otherwise healthy individuals.

Reference: “The Toxoplasma effector GRA28 promotes parasite dissemination by inducing dendritic cell-like migratory properties in infected macrophages” by Arne L. ten Hoeve, Laurence Braun, Matias E. Rodriguez, Gabriela C. Olivera, Alexandre Bougdour, Lucid Belmudes, Yohann Couté, Jeroen P.J. Saeij, Mohamed-Ali Hakimi and Antonio Barragan, 28 October 2022, Cell Host & Microbe.

DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.10.001

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Olle Engkvist Byggmastare Foundation, ProFI, the Chemistry Biology Health (CBH) Graduate School of University Q13 Grenoble Alpes, Laboratoire d’Excellence (LabEx) ParaFrap, the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, and the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale.

Share your story or advertise with us: Whatsapp: +2347068606071 Email: info@newspotng.com